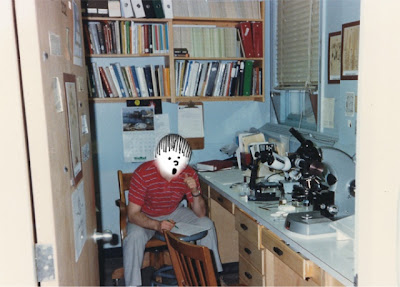

The author in his man cave... er, office, on a more or less neat day, ca 1986.

Many scientist's offices are more or less like caves. As careers extend to years and then decades, a sedimentary process occurs, and notebooks, cerloxed reports, binders, duotangs, photocopies and mysterious obsolete equipment form strata on all horizontal surfaces. Forget this image of the scientist as a highly organized, left-brained filer of information and data. Many of us do have good spatial memory, which means we often can find that exact piece of paper about 3 cm from the bottom of that specific pile of paper on the second shelf behind that old typewriter. But if it is not there, if someone has moved it, or actually filed it in a folder somewhere, we're in trouble. A big worry, which grows by the year, is that a minor earthquake, or centrifugal forces released by the spinning of the earth, may tip a stack of paper, unleashing a domino effect that will bury us beneath our treasured journals. Or record albums... One of my earliest profs had a classical music collection that overflowed from his house into his office, thousands of LPs, and a state of the art stereo system, which pushed all the scientific paper out into the main lab. The ecstatic opera arias also kept the students away.

The chemist in the first place I worked shared his office with his technician. He also shared the office with tall, misshapen, dark green filing cabinets and an old

paper chromatography tank that he could not bear to throw out. The tank was about a metre tall and broad, perhaps 50 cm wide, made of thick translucent plastic, with a tight lid. It was used to hold big sheets of chromatography paper, which were suspended from long glass rods so that one end rested in a smelly solvents; it was used to separate chemicals in mixtures, just as children separate colours in ink using tissue paper. The technique was hardly used by then, but our chemist thought the method might come back. In the meantime, the tank made a good surface to pile things on. His technician collected rocks, so his corner of the office had various stones and boulders that he was showing off, or waiting to clean with horrible chemicals during his breaks.

My own office, shown above, had once been a closet, a long and narrow extension of the main lab. A counter top ran along the window wall, ideal for piles of papers and specimens. We got computerized fanfold printouts of abstracts in those days, the latest in science personalized for our own interests (at 2 cents per item) delivered automatically every week, where most of us tossed them into a pile in the corner. Some colleagues obsessively separated all the pages and removed the tractor feed margins, and dutifully filed them in filing cabinets with drawers sized just for this purpose. I have inherited a few of these literature indexes from retired colleagues; I never use them but it would be a shame to throw them out. Whether my employer at the time was aware of it or not, I have a strong tendency to fill all available space with treasure, and my tube-like office prevented excessive spreading. For a short period of time, I explored the benefits of

Power Napping, after reading suggestions that it enhanced productivity. Having a lockable door was a useful novelty.

Once upon a time, senior scientists had their own secretaries. Outside of many offices of that vintage, there was a small nook for a typewriter, where the secretary would sit and tap away at letters, manuscripts, and 3x5 file card indexes (in the days before the computerized searches). By the time I joined the scientific workforce, this was a thing of the past, but there were still colleagues who complained about having to wait for the manager's secretary to find the time, or even worse, had to do their own typing. When I 'designed' my present office, I liked the secretarial nook so much that I incorporated it in the plans. Rather than wall off the whole space, I left half of it open to the lab, thinking I could have my own little labette for my personal activities, where the students and technicians would not be allowed. Of course, I now mostly pile up paper, boxes, old film cameras and specimens there.

No one teaches us in grad school how to file things. Eventually, I learned to have a file for everything, every student, every idea, every project, every committee, every proposal, every manuscript. Most scientists don't like to put things in filing cabinets until they are finished with them. The 'out of sight, out of mind' concern seems quite common. Thus, we have filing cabinets that we put things into, but seldom take things out of. We all learn about the physical forces present in horizontal stacks of paper, and how to compress and force new documents into the collection (surely someone has invented a tool for this). You'd think the filing cabinet drawers would eventually explode from these forces, but I've never heard of this happening. Instead, when the filing cabinet is truly full, we begin stuffing valuable historical documents into files on shelves instead.

My career corresponds with the microcomputer revolution. I was a grad student when the first Apple II+ became available. At first, no one really knew where to put the computers, or especially the printers, which at that time were both rather large. They tried to cram an extra table into the office, maintaining the fiction that the desk itself, and paper and pens, still had an independent function. My main memory of my MSc is of my supervisor swearing at the daisy wheel printer that occupied half the horizontal space in his office, either because the paper was misfeeding, or because the daisy wheel had broken an arm, printing a forty page manuscript without the letter 'e'.

My present office is in a transitional state. Some of my colleagues have very minimalist spaces. The most conspicuous feature of one friend's office is the artwork created by his wife, and of another's, photographs, paintings and souvenirs accumulated during his travels. With electronic journals and books, we now accumulate much less paper, and it is much easier to stuff things onto a hard drive than into a filing cabinet. Even if most of the accumulation has stopped, it will take at least a decade to go through everything in my office, digitize what should be digitized, discard what should be discarded, and indicate what should be passed on or archived in some way. On one hand, I don't want anyone else to have to go through all of this stuff. On the other hand, I'm concerned about preserving unique knowledge and there are lots of unpublished observations, facts and data hiding there. So I go through old files, discarding drafts of manuscripts and peer reviews of papers published twenty years ago, minutes of meetings that were irrelevant even when they were being written, floppy disks that can no longer be read, unfocused photographs and banal correspondence.

The important stuff goes onto the hard disk. The hard disk on the laptop becomes the new repository for our knowledge and our scientific lives. It can all be reconstructed from there, if anyone cares to do so, as long as no one decides just to wipe my hard drive when I finally retire. After all, as I said, no one teaches us how to file things, and computers are just as bad as geologically stratified offices. They are full of mysteriously named and duplicate files, version after version of manuscript drafts, and archived email messages and spam. But at least if a hard drive falls on you, you won't get buried. Psychologically maybe, physically no. That's progress, I think.