It was a lab rule that anyone giving a talk had to have a practice

run with the prof. This was supposed to be one on one but when my turn came, it

didn't work out that way. Dr. L. was in deep denial about computers, but always

wanted to impress colleagues with his state-of-the art knowledge of the latest

technology. My talk had to use some LINUX

presentation program with vertigo-inducing animation capabilities that Dr. L. found

on a CD-ROM in some old magazine. And this meant that Dennis had to be there

for the dry run. He could run any program on any computer. He had bytes in his

fingernails.

"Now

Peter," Dr. L told me as I was ready to start. "This is your first conference

presentation. I want you to be well prepared. Don't be frightened, but the crowd

at some of these meetings is like a hoard of vultures, just waiting to tear meat

from your limbs. Especially Kowzlowski... that cow. You've got to look

sharp."

"Uh,

okay," I said, glancing over at Dennis, who gave me his finest gap-toothed

smile. "Can I begin?"

"Please

do."

The computer

was balanced on a stool wheeled in from the lab. "Well, here's my first

slide."

"Is

that how you're going to start?"

"No, I

was just..."

"Say it

how you're going to start."

"Good

afternoon, ladies and germs. My topic for my presentation..."

"Hold

on. Ladies and germs?"

"They're

microbiologists. It's a joke."

"No it

isn’t. Don't tell people what the topic is. They can read."

"I'd

like to talk about the results from my first year of thesis research..."

"Dennis,

I don't like the background on that slide. Is it green?"

"No,

it's red," Dennis answered.

"Let's

try it blue."

"No

problem." Dennis clicked the mouse around on the stack of journals that

was the most uncluttered horizontal surface in the room. I realized then that

the dry run of my ten minute talk would last at least two hours. None of the slides

were right, they either had too much text or not enough. He didn't like the

bullets... we had a ten minute discussion on whether they should be round or

square. And he wanted me to refer to more of the lab's previous results in the discussion.

"Okay,

that's not bad, Peter," he said when I finally reached the end. "Now,

let's see if you can handle the questions. Let's see... Dennis, can you think

of anything?"

"No,"

Dennis answered. He looked so much like some hippified version of Alfred E.

Neumann, I had to laugh. He often used imaginary words and made cartoonish

sound effects. This time he just gave me a wink.

"What

kind of question would that Kowzlowski ask?" Dr. L. wondered. "That

cow. I know. In your fifth slide, weren't the correlation coefficients too low

for you to make such sweeping statements about the relationships between your

variables?"

I glanced

warily at Dennis. In addition to his Luddite approach to computers, Dr. L. was known

for his utter ignorance of statistics. "That's a principal coordinate

analysis," I told him. "I didn't do any correlation analyses."

It was

nearly four when we escaped. "I don't know what I'm going to do," I

told Dennis. "He made you change every slide. I’ll have to relearn the talk,

it's all different and I'm speaking tomorrow."

"Don't

worry. I saved the originals. You could never use the new ones... he's colour

blind, didn't you know? I was just humoring him. Have you ever seen him talk? Holy neeble. You'll be fine as

you are. But Kozslowski's going to have you for breakfast."

"Is she

really that bad?"

"I've

never met her but he's been ranting about her for years. The happiest I've ever

seen him is the day he got one of her manuscripts for review. As far as I can

tell, her lab does exactly the same work that we do, but they use a different

bug."

"I

don't know, Dennis. I just want to concentrate on presenting my data. How bad

can she be?"

Celia and I

handled the registration table the next morning. It was strange to suddenly

have faces to match the names I'd known only as authors of papers. No one

looked like they should. Dr. Needles was short and balding. Dr. Reid, who often

wrote long, ponderous sentences full of vaguely alien syntax, turned out to be

a woman. I half expected Dr. Kozslowski to be a rotund lady with a large nose,

corresponding with Dr. L's nickname for her. Perhaps she would even be wearing a

white dress covered with large, black spots.

"Peter!"

Dr. L. half-shouted at me, panting and red faced. "It's getting hot in

here. Go see if you can find some air conditioners. Celia can handle the

desk."

Dr. L. was notoriously

frugal and had booked the cheapest room on campus. He hadn't anticipated a heat

wave at the beginning of June. I searched from lab to lab, accompanied by some

undergrad muscle. No one wanted to part with their portable air conditioners,

but we scrounged four units from our own lab and one of the teaching labs. When

we got back to the conference room, the first session was already underway. They

had opened the windows and turned on some fans to set up a cross breeze. A

nervous little man with an Australian accent was finishing what had obviously

been an awkward presentation. He was using overheads for visuals; gusts of wind

kept blowing them off the projector onto the floor.

"How's

it going?" I asked Celia.

"Kozlowski

lit into Dr. L. after his opening monologue. Claimed he didn't acknowledge her

as the first discoverer of the Q factor."

"Which

one is she?"

"I

don't see her now."

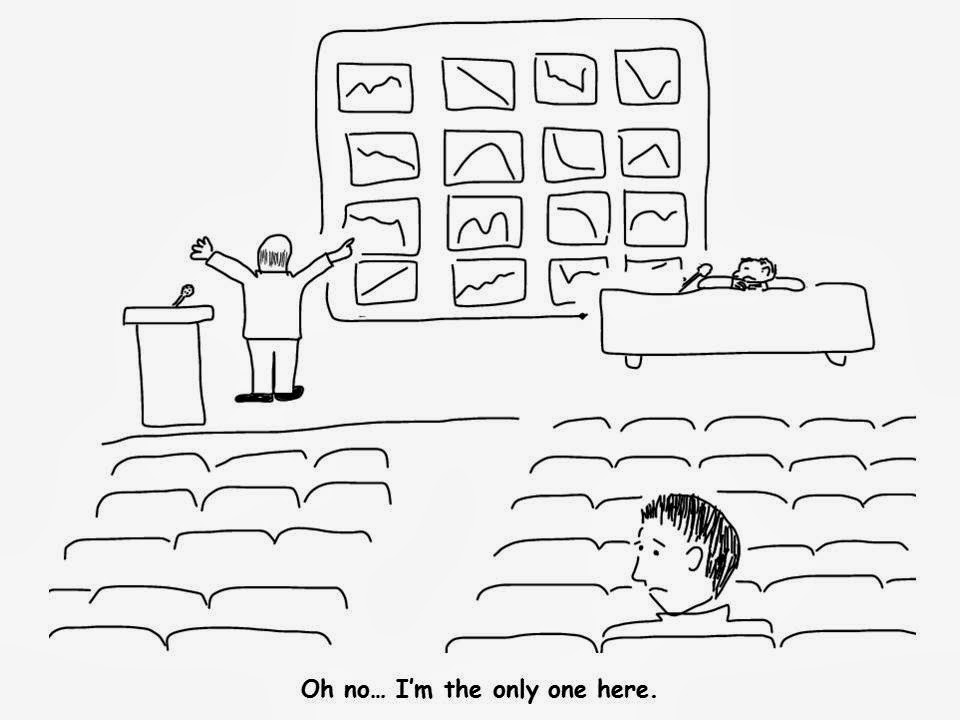

My talk was

first after the coffee break, and I tried to simultaneously calm and psyche

myself with all that familiar advice about giving seminars:

a) Check

your fly before going to the podium.

b) Check

your hair in the mirror for cowlicks.

c) Don't

wash your hands in case you accidently splash water on your trousers.

Dr. L.

introduced me and there I was, trying to remember my opening lines. They had

forgotten to plug in the laptop, of course, and the battery died just as I was

about to begin.

d) Always

smile at the audience.

All my Milton

Berle jokes evaporated as I waited for the title slide to appear. Two or three

people fussed around the computer while two or three others rushed over to stop

one of the air conditioners from tipping out of the window. At last, the screen

came to life, and I launched into my maiden speech. I can hardly remember

anything I said. It seemed like someone else speaking. I watched the overheated,

jet-lagged delegates struggling to stay awake, a few rocking side to side,

suffering the diuretic effects of too much coffee.

A hand was

up in the audience. The chair nodded, and the woman asked, "Can you relate

your results to the oppression of the women in patriarchal societies or the

fall of the Berlin Wall?"

"Pardon

me?" The questioner was a petite woman with a strong New York accent. Short

brown hair, kind of pretty beneath the thick glasses.

"What I

mean is, is this work actually relevant to anything? Does it have any

significance to the plight of humanity on this planet? You haven't shown us

anything we don't already know..."

"This

is only preliminary data. I'm just starting my thesis, there's still two more

years to go..."

The woman

snorted and folded her arms. Everyone seemed to be alert and embarrassed. Finally,

someone at the back of the room put me out of my misery with a banal question

about the number of replicates in one of my experiments.

I sat down. I

had lost my scientific virginity. Instead of feeling excited and fulfilled, I had

been a sacrificial lamb to a vampire cow.