Today, I'm on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, number six on the list of institutions with the most Nobel Prize winners. I wanted to know if there were statues or monuments to honour these famous people. The reply was that laureates are offered a choice of having a building named after them or their own permanent parking place, and that they all choose the parking space. Here are some of them are in front of the Physics Building on Oppenheimer Way. Notice that the display of a parking permit is required to prove status. Such permits probably don't help them find parking at the grocery store, where expectant mothers are far more important. Very few of the laureates are at work today. They must have heard I might be dropping by.

Thursday, 20 March 2014

Parking for the elite

Today, I'm on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, number six on the list of institutions with the most Nobel Prize winners. I wanted to know if there were statues or monuments to honour these famous people. The reply was that laureates are offered a choice of having a building named after them or their own permanent parking place, and that they all choose the parking space. Here are some of them are in front of the Physics Building on Oppenheimer Way. Notice that the display of a parking permit is required to prove status. Such permits probably don't help them find parking at the grocery store, where expectant mothers are far more important. Very few of the laureates are at work today. They must have heard I might be dropping by.

Monday, 17 March 2014

Sitting ovation

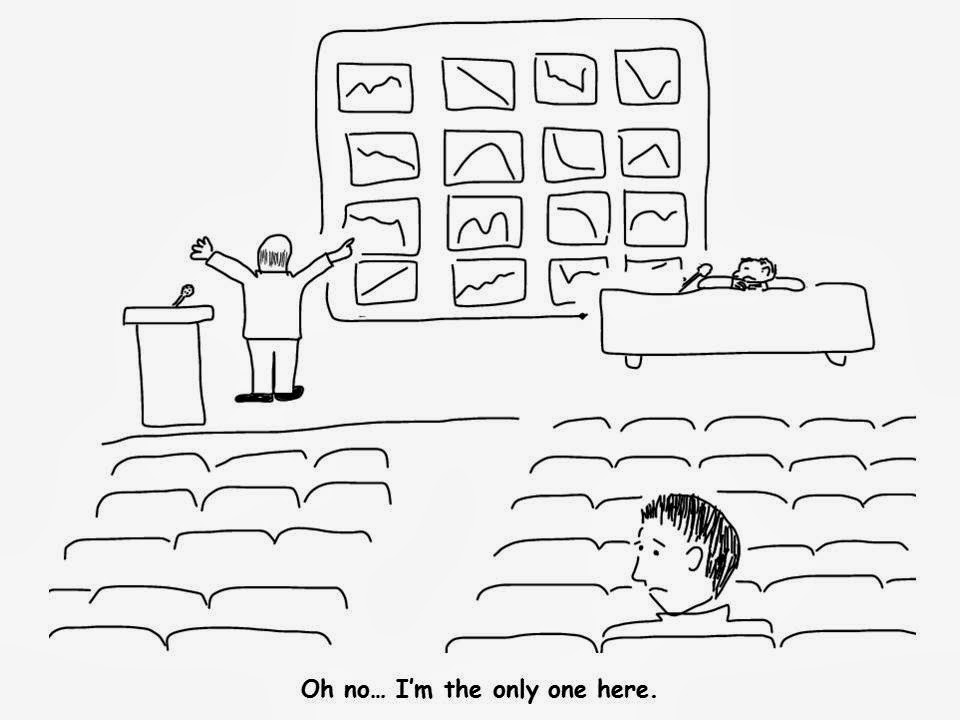

Perhaps as an expression of some latent compulsive behaviour, I tend to count things. So I can tell you with certainty that at a typical scientific conference or seminar in my field, audience members clap their hands an average of 13 times as their contribution to the applause. It may be a coincidence that the average grapefruit has 13 segments. Perhaps a fully developed grapefruit should have sixteen segments (the sphere divided by 2 by 2 by 2 and then 2 again), and three tend to abort. Whether there is a correlation between applause for scientific presentations and grapefruits segments, I leave to your imagination and creativity with freakish statistics to explore.

We were at a concert recently in a small club, and the warm up act got about 26 claps after every song. This is twice as many as a seminar and it happened after every song, so every five minutes or so. Last night, the main act got 26-36 claps after most songs, and as many as 50 to reward those special moments. The only logical conclusion is that if you crave generous applause, be a musician and not a scientist. Imagine a world where the audience claps at the ends of the Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion of every research presentation, and goes wild over a particularly astonishing graph. This could be disruptive, but we'd get used to it.

Research seminars range from about six minutes long in intense specialist conferences to 45 minutes for keynote or banquet speakers. My longest talks have been university lectures, where I might drone on for 80 minutes while students surf the Internet or send Tweets that I fortunately never have to read. I'm just a guest lecturer and nothing I say ends up on their exams so all they need to do is sign the attendance sheet. They sometimes applaud out of some sort of vaguely perceived pity. About six claps, twice as many as that most sarcastic of applause, three staccato claps.

A scientific analysis of applause was published last year. The authors compared the spread of clapping to a 'social contagion'. In other words, applause spreads like a virus, with one or two people infecting everyone else, and after the appropriate time, the applause dissipates in the reverse way. Perhaps it is only a matter of time before some scientist employed by some megalomaniac politician engineers a virus that can be released on unsuspecting crowds to increase clap counts.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)